Domalde was a tragic Swede king described in the 9th century. His mother had cursed him with bad luck, which carried to his people, who were having bad harvests. As the story goes:

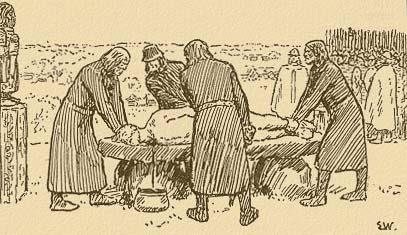

Domald took the heritage after his father Visbur, and ruled over the land. As in his time there was great famine and distress, the Swedes made great offerings of sacrifice at Upsalir. The first autumn they sacrificed oxen, but the succeeding season was not improved thereby. The following autumn they sacrificed men, but the succeeding year was rather worse. The third autumn, when the offer of sacrifices should begin, a great multitude of Swedes came to Upsalir; and now the chiefs held consultations with each other, and all agreed that the times of scarcity were on account of their king Domald, and they resolved to offer him for good seasons, and to assault and kill him, and sprinkle the stalle of the gods with his blood. And they did so.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domalde

This idea of king sacrifice is intriguing. It takes head on a contradiction inherent in the idea of a king, the most valuable person. If they’re so valuable, and if sacrifice is about giving up valuable things, then naturally a king is who you murder once murder of less valuable things has failed. King Sacrifice is important to distinguish from chaotic regicide by the masses. Domalde didn’t just face an uprising or revolt, he was sacred and therefore sacrificial. Or not. Maybe it’s just a story. Maybe some mere uprising or revolt got dressed up as having a deeper purpose to make the people look less barbaric. But the trope of the Sacred/Sacrificial King, evident in examples such as Rex Nemorensis, the scapegoats of myth, and obviously Christianity, gives us a look into a world before Kings merely had a divine right to rule, when they had a divine responsibility, enforced by all people, to rule well.

The theme of King Sacrifice—in which the benefits of power are structurally outstripped by its risks and responsibilities—has great implications for governance design, a concern of mine. King sacrifice creates a frame in which leadership is inherently thankless, accountable, and fraught: an ideal environment for selecting responsible leaders.

The prompt

Once you have experienced the failures of strong leadership and the failures of extreme decentralization, you may converge on a specific place in the middle: “We should have leaders, but not anyone who wants to lead.” The collective wisdom is that reluctant leaders are more like followers. They are humble, empowering, and their use of power is seen as responsible and legitimate because everyone understands that they don’t like using it.

So let’s say we all agree: “We should have leaders, but not anyone who wants to lead.” What then? It’s a great if you happen upon the rare someone like that, but in practice they simply can’t be found and recruited reliably. Whether you’re a community group or a large firm, it’s the luck of the draw for you: to have the right person around with the right attitude and alignment, you get lucky or you don’t. In that way, the maxim is more of a description than a strategy for good centralized governance.

Of course, it would be different if we could find or create reluctant leaders. If there were a way to reliably and systematically produce and select reluctant leaders, we’d be one step closer to saving dictatorship, while creating a dictatorship that’s worth saving.

The first thing to do is break this dichotomous construct “reluctance”. It presumes that a candidate is either entirely power hungry or entirely power wary. But how a person is depends on where they are. We know that power-wary people can eventually a develop a comfort for and fluency with power that can start to look like a taste for it. And we know that many traditional authority-focused leaders can have eye-opening experiences that inspire them to open up and flatten out. We also know that your reluctance depends on simple things like how full your plate is.

Let’s take advantage of context to create reluctant leaders. And under a framing of king sacrifice, it isn’t difficult. We need to step away from a picture of leadership as providing access to power and control, in favor of the view in terms of service and collaboration. For the right person, a big sacrifice counterbalances the benefits of power and control, leaving only the value of learning and serving others.

Imagine a small group election in which each candidate has to explicitly demonstrate their reluctance, and convince people to vote for them on the faith that they don’t really want to do it. More precisely, imagine an election in which every candidate describes what they are sacrificing in order to lead.

People who already don’t want to lead will already see that they are making a sacrifice, and can just describe it. People who do want to lead, and would naturally sacrifice anything, can make themselves actually reluctant by proposing a big sacrifice that they will make if they take the position. They will take a pay cut, they will never force anyone to do anything, they will get a therapist, or make themselves recallable with a minority vote, or pay out of pocket toimplement a program that reduces the authority of the position by spreading power around.

The community will then evaluate each candidate’s sacrifice along with every other qualification of holding the position. Whether the sacrifice is big or small or credible or not can’t really be quantified in general, so it’s a subjective or political decision on the part of voters whether a person’s sacrifice is substantial and legitimate enough. But even then, the political process is more responsive to arguments that are credible, and a goal is credible that meets recognized goal evaluation criteria. One example is the SMART taxonomy, which helps you ask: Is the proposed sacrifice not just substantial, but Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound?

Can this sacrifice framing mechanism be gamed? Well it’s political, of course it can be gamed. This is why it’s important to assume constrained contexts, such as an organization that is small enough that it can maintain alignment and rely on social factors like trust, respect, reputation, and just deeper knowledge about the person. Whether a pay cut is a sacrifice or a token depends on inside knowledge about the person and their existing means. It’s up to the community to know their candidates well enough to know if sacrifice is being invoked authentically or only rhetorically.

Of course, I’m coming from a specific place, defining leadership as shared or cooperative leadership, dictatorship as simply unitary authority, potentially benign. It can be captured by the power hungry, but doesn’t serve them by definition. And I’m assuming a group with a basic level of mutual regard and goal alignment. So these aren’t general claims, but claims that make sense for a group that is small enough for social norms to play a role in how things work.

Where is all this coming from?

Aside from the noble project of Saving Democracy, I’ve got a side hustle of Saving “Dictatorship”. It’s not such a betrayal:

- Systems based on authority and leadership are pragmatic, workable, and familiar.

- They are the easiest social systems to design and implement and scale (explaining why they’ve taken over the world)

- If you can keep them benevolent, they can also be surprisingly democratic, in the sense of integrating the needs of all stakeholders, if you define benevolence to require it

- Power and coercion are bad, they often co-occur with authority and hierarchy, but they can be decoupled. Successfully decoupling them puts unitary structures on the map as democratic solutions. That separation has to happen both in an org and in everyone’s minds

- While people think of leadership and democracy as opposed, I think they’re aligned. As I define those terms, strong participation is a result of strong leadership, and strong leadership is a result of strong participation. They’re no dueling alternatives to the distribution of power, but two sides of the same coin of universal empowerment.

- Taking it all the way, I actually don’t trust a democracy to work if every member of it hasn’t had a lot of experience leading. Making unitary authority systems of every size more capable of care and accountability makes it easier to give more people more experience in leadership.