I made a site this summer—http://whatsyoursign.baby—that’s a sort of glorified blog post about what happens when you go ahead and give astrology a basis in science. I wrapped it up with an explainer that was hidden in the back of the site, so I’m publishing the full thing here.

The history

Before the 17th century, Westerners used similarity as the basis for order in the world. Walnuts look like brains? They must be good for headaches. The planets seem to wander among the stars, the way that humans walk among the plants and trees? The course of those planets must tell us something about the course of human lives. This old way of thinking about the stars persists today, in the form of astrology, an ancestor of the science of astronomy that understands analogy as a basis of cosmic order.

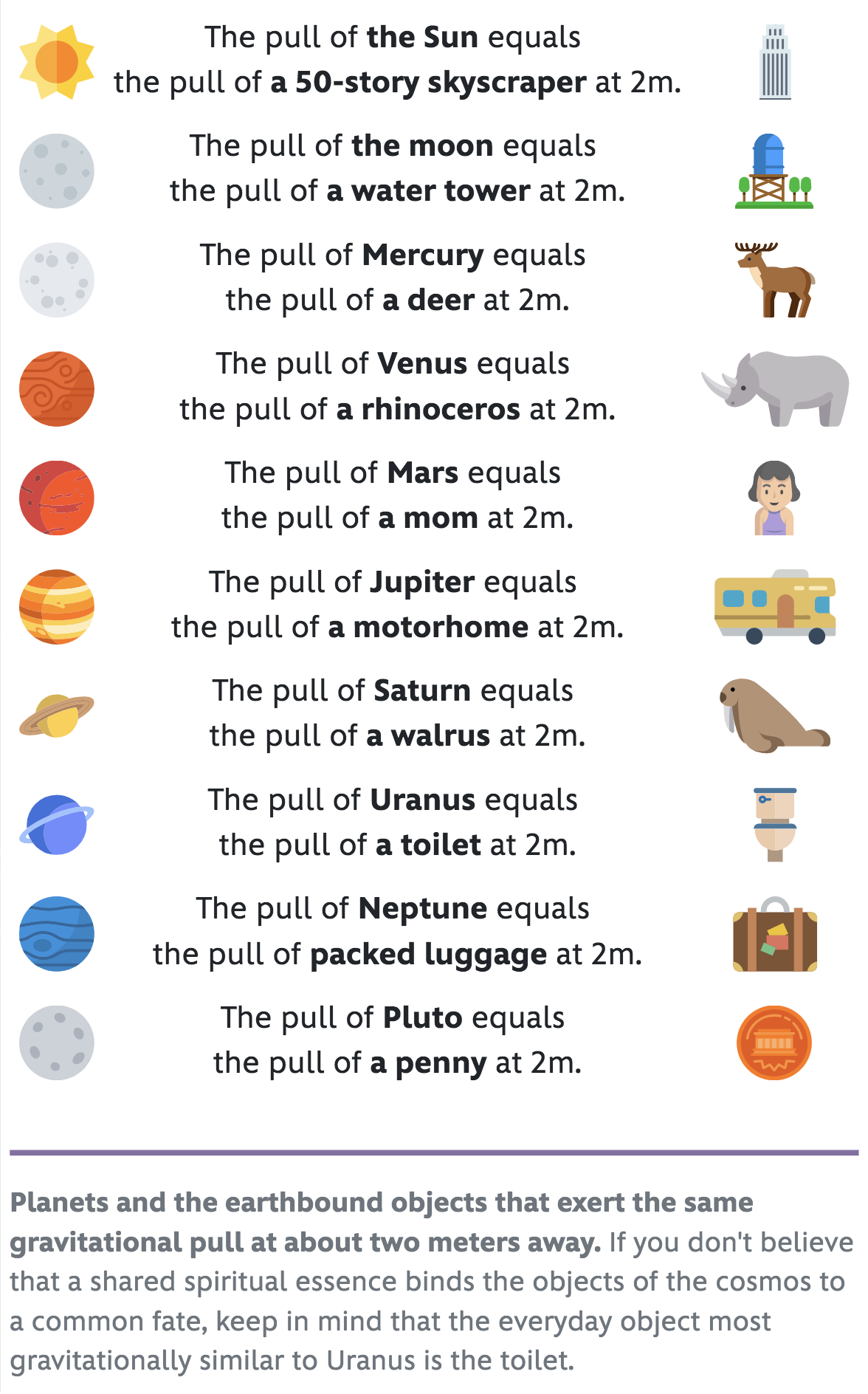

Planets and the earthbound objects that exert the same gravitational pull at about two meters away. If you don’t believe that a shared spiritual essence binds the objects of the cosmos to a common fate, keep in mind that the everyday object most gravitationally similar to Uranus is the toilet.

It was our close relationship to the heavenly bodies that slowly changed the role of similarity in explanation, across the sciences, from something in the world to something in our heads. Thanks to the stargazers, similarity has been almost entirely replaced by cause and mechanism as the ordering principle of nature. This change was attended by another that brought the heavenly bodies down to earth, literally.

Physics was barely a science before Isaac Newton’s insights into gravity. But Newton’s breakthrough was due less to apples than to cannons. He asked what would happen if a cannonball were shot with such strength that, before it could fall some distance towards the ground, the Earth’s curvature had moved the ground away by the same amount. The cannonball would be … a moon! Being in orbit is nothing more than constantly falling! Through this and other thought experiments, he showed that we don’t need separate sciences for events on Earth and events beyond it (except, well, he was also an occultist). Newton unified nature.

Gravity—poorly understood to this day—causes masses to be attracted to each other. It is very weak. If you stand in front of a large office building, its pull on you is a fraction of the strength of a butterfly’s wing beats. The Himalyas, home of the tallest peak on Earth, have enough extra gravity to throw off instruments, but not enough to make you heavier. Still enough to matter: Everests’s extra gravity vexed the mountain’s first explorers, who couldn’t get a fix on its height because they could couldn’t get their plumb lines plumb.

So is the gravity of faraway bodies strong enough to change your fate? And if so, how? Following the three-century impact of science on thought, modern astrologists have occasionally ventured to build out from the mere fact of astrology into explanations of how it must actually work; to bring astrology into nature right there with physics. Most explanations have focused on gravity, that mysterious force, reasoning that the patterns of gravitational effects of such massive bodies must be large, unique, or peculiar enough to leave some imprint at the moment of birth.

But by making astrology physical, we leave open the possibility that it is subject to physics. If we accept astrology and know the laws of gravity, we should be able reproduce the gravitational fingerprint of the planets and bring our cosmic destiny into our own hands.

Refs

Foucault’s “The order of things”

Bronowski’s “The common sense of science”

Pratt, 1855 “I. On the attraction of the Himalaya Mountains, and of the elevated regions beyond them, upon the plumb-line in India”