I would love to be optimistic about the future. In fact, I’m actively trying. There is hope in stunning technological advances, the existence and development of progressivism, and all the license we have to abide by some lessons of history (that human potential overall gets higher) and potentially ignore others (the inevitability of resource conflict). We can imagine ignoring dark lessons of history because modern humanity has demonstrated its ability to change how it is. We’ve changed in the last 100, 50, 10, or even 5 years more than we did over thousands of our earliest years. Maybe scarcity is a solvable problem. For example, I’ve been following with awe and wonder the rapid, exciting progress of the Wendelstein 7-X experimental fusion reactor in Greifswald, Germany. The limitless energy of hot fusion, and several other emerging technologies, means that we can think about energy intensive technological solutions to otherwise forbidding problems, toward the availability of costly fresh water from sea or waste water, the availability of sufficient food and wood from ever higher input agriculture, the possibility of manually repairing the climate, undoing material waste by mining landfills and the ocean’s trash fleets, and accessing the infinite possibilities permitted by space. These things could all be in hand in the next few decades, no matter how destructive we are in the meantime. Allowing these possibilities means very actively suppressing my cynicism and critical abilities, but I think it’s a very healthy thing to be able to suppress them, and so I try.

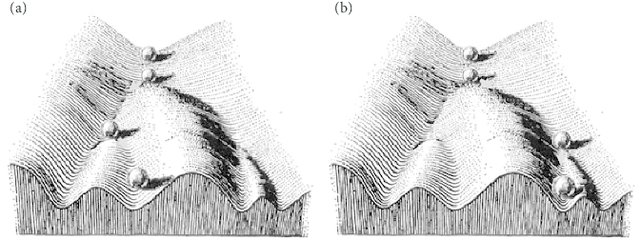

But every argument I come up with for this rosiest view backfires into an argument against postscarcity. Here’s an unhopeful argument that I came up with recently, while trying to go the other direction. It has a few steps. Start by imagining the state of humanity on Earth as a bowling ball rolling down the lane of time. Depending which pins it hits, humanity does great, awful, or manages something in between. There are at least two gutters, representing states that you can’t come back from. They foreclose entire kinds of future path. Outside of the gutters, virtually any outcome for humanity is on the table, from limitless post-humanity to the extinction of all cellular life on earth. In a gutter, a path has been chosen, and available options are only variations on the theme that that gutter defines. The most obvious gutter is grim: if we too rapidly and eagerly misspend the resources that open our possible paths, we foreclose promising futures and end up getting to choose only among grimmer ones. A majority of climate scientists assert that we are already in a gutter of high global temperature and sea levels. There is also a hope gutter, in which technology and the progressive expansion of consciousness will get us to an upside of no return, in which only the rosiest futures are available, and species-level disaster— existential risk— is no longer feasibly on the table.

The doom gutter is the easier to imagine of the two, and therefore it is easier to overweight. It’s too easy to say that it is more likely. “You can’t envision what you can’t imagine.” The question to answer, in convincing ourselves that everything is going to be fine, is how to end up in the hope gutter, and show that it’s closer than anyone suspects. That’s what I was trying to do when I accidentally made myself more convinced of the opposite.

The first in my thinking is to simplify the problem. One thing that makes this all harder to think through is technology. How people use technology to imagine the future depends a lot on their personality and prior beliefs. And those things are all over the place. From what I can tell, comparable numbers of reasonable people insist that technology will be our destruction and salvation. So my first step in thinking this all through was to take technology out: humanity is rolling down the gutter of time with nothing beyond the technology of 1990, 2000, or 2020, whatever. Which gutter are we mostly like to find now? Removing technology may actually change the answer a lot, depending where you come from. I think many tech utopians, as part of their faith that technology will save us, also believe that we’re doomed without it. I’ve found tech optimists to be humanity pessimists, in the sense that, if brave individuals step up to invent things that save us, it will be despite the ticking time bomb of the vast mass of humanity.

I, despite being a bit of a tech pessimist, am a humanity optimist. I think if technology were frozen, if that path was cut off from us we’d have a fair chance of getting our senses and negotiating a path toward a beautiful, just, empowering future. Especially if we all suddenly knew that technology was off the table, and that nothing would save us but ourselves. I don’t think we’d be looking at a postscarcity future, there is no postscarcity without seemingly magical levels of technological advancement, but one of the futures provided by the hope gutter. Even without technological progress, changes in collective consciousness and awareness and increases in the space of thinkable ideas can and have had a huge influence on where humanity goes. Even without the deus ex machina of technology, it is still possible to have dreams about wild and wonderful possible futures. This isn’t such a fringe idea either. Some of my favorite science fiction, like Le Guinn’s “Always Coming Home,” takes technology out of the equation entirely, and still imagines strange and wonderful perfect worlds.

So without technology, I actually see humanity’s path down the bowling lane of time being a lot like the path with technology: we have a wide range of futures available to us, some in the doom gutter, some in the hope gutter. That’s a very equivocal answer, indisputable to the point of being meaningless, but it’s still useful for the next step of my argument.

I do not think technology is not good. It is not bad. It doesn’t create better futures or worse ones. It overall just makes things bigger and more complicated. One quip I use a lot is that Photoshop (an advanced design technology) made good design better and bad design worse. Nuclear science created a revolution in energy, and also exposed us to whole new kinds of bitter end. Genetic engineering will do the same. Even medicine, possibly, if it ends up being able to serve the authoritarian ends of psychology-level social control. So unlike most people, I don’t think technological advances will bias humanity into one gutter or the other. I think technology will expand the number of ways for us to get into one gutter or the other. And it will get us into whichever gutter faster. That’s step two.

Step three of the argument starts with my assumption that the doom gutter is closer than the hope gutter. It is without technology, and it is with technology. I started off by saying that we should avoid saying that because it’s easy to say. But even then, I still think so. That’s just my belief, but this is all beliefs. One of the few clean takeaways of the study of history is that it is easier to destroy things than create them. But doom, in the model I’ve built, isn’t more likely because of technology, only because it is more likely overall. That doesn’t mean that technology will have no effect. It will bring us more quickly to whichever gutter it is going to bring us to. If at the end we’re doomed or saved because of technology, that end is less likely to happen slowly, and less likely to be imaginable.

p.s. I’d love to believe something different, that technology will save us. I’ll keep trying. We’ll see.