Puns are the lowest art. They’re easy and hammy, remarkable only for representing the biggest missed opportunity in humor: they’re as funny are you can get without being in any way funny.

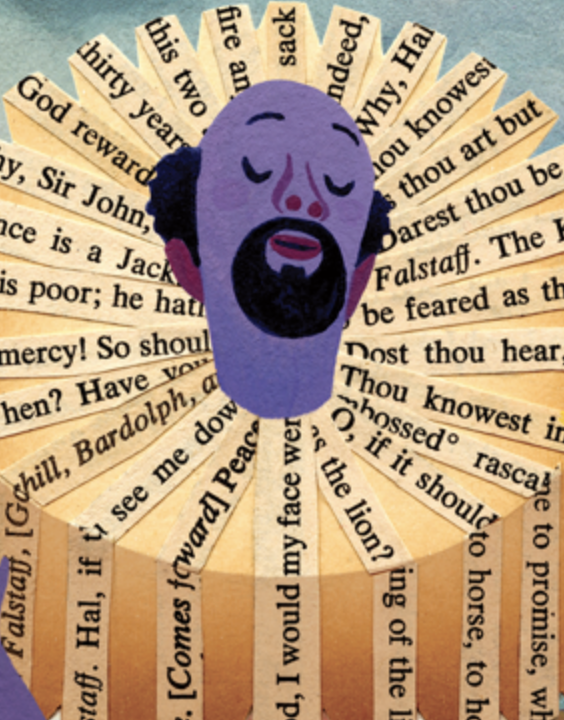

So imagine how delightful it is that you’ve got right there, right next to punnery, the highest art of all: almost-punnery. You all-but say a pun, enough to make others make the final step and think them. Shakespeare scholar Stephen Booth called them “unexploded puns,” and argued that they were the root of Shakespeare’s genius (as Jillian and I laid out in Nautilus Magazine).

Booth’s cleanest example was from Longfellow’s poem Hiawatha’s Childhood

Rocked him in his linden cradle,

Bedded soft in moss and rushes,

Safely bound with reindeer sinews;

Stilled his fretful wail by saying,

“Hush, the Naked Bear will hear thee!”

“Naked bear”?! You mean “Bare Bear”!!! Except Longfellow didn’t make the pun. He could have. Instead, he makes you make the pun. Maybe not consciously, maybe not on any level at all. He just lays it out there, an opportunity to give your brain a little pop, take it or leave it. It’s like a pun, but with restraint, economy, and style: none of the bad of punnery, all of the good, and then some.

Or maybe there’s nothing there at all. Maybe by naked bear Longfellow just meant naked bear, no grin on his face, and Booth is reading into it too much. That doubt adds to the tension that makes almost puns great: you get to add some tension play to the mix by planting the pun with subtle suggestions that you seem to know it’s there. In Longfellow’s case, the Hiawatha poems don’t rhyme, so you can’t argue that he was in the rhyming headspace that would have made “bare bear” obvious. But “naked bear” is pretty redundant. Bears are naked. Syllables cost space, and you don’t spend them to say things that you’re not trying to say. In fact, what better way to spend them than make your reader generate even more: “Naked bear … bare bear!”; five syllables for the price of three.

Now there’s no proving the author’s intentions, and where you can the effect is ruined. With proof you experience the author as wink-winky, and suddenly “naked bear” is no better than a pun. And when there’s doubt, another thing happens: you start questioning and digging in everywhere, concerned that you’re missing something, that there’s more. By being doubtful and withholding, almost puns created the experience of poetic richness.

Playing with almost puns

My own biggest exploit was in grad school. I had a colleague who was working really hard at his desk. It was a tiny desk in a tiny office, so he was crammed right up against the wall, his forehead just a couple feet from an anatomical drawing of testicles I had given him, a leftover from a recent exhibit on historical medical texts I had helped break down.

The setup for the pun was right there, pristine. I could just stand there in the door, turn the ham turned all the way up, and yell: “Hey, you’re really BALLS TO THE WALL!!!” He’d jump him out of his seat.

But I didn’t do that. Instead I spent the next 15 minutes setting it up, crafting the conversation, nudging and covertly cajoling, trying to get him to say it to me.

“Hey buddy, you’re really working hard, huh? I see you put the drawing right there in front of you on the wall. Gee, you’re really getting a lot done. It’s funny that your desk is facing that way, and not the window. Are you more productive that way? You know, I never took a good look at it though, is that pubes? I can’t tell from here. Wow, you’re almost up right against them. I hope I’m not interrupting; you must be busy.”

Eventually, with a lot of work, he gets this stupid grin on his face and says “Oh, you bet! I’m really BALLS TO THE WALL!!!” It’s probably one of the triumphs of my life

Playing with almost puns with others

And that’s not even the good part. I once lived with several others who’d learned the same aesthetic. We’d all taken Booth’s class, It ended up that we were always trying to pull puns out of each other, in every conversation. Eventually puns were never said and always thought. To the outsider, you can imagine you’re standing among these nerds having a normal conversation, except they won’t stop with the wicked shared glances, and you can help but wonder if something’s going on.

It was a lot like that joke about the old-timers who have been telling the same jokes for so long that they now tell them by number: “62! Har har har. 87! Har har har.” You’re telling the joke and nailing the punchline without telling the joke or nailing the punchline.

It’s in that cohort of Booth fans that I got the closest I’ve ever been to a separate plane of shared meaning. The bond was amazing, all due to unsaid word play. It was mind reading. So much more than a pun.

That’s it. As far as I’m concerned it’s the highest art form. Incepting puns. I only regret we don’t have a good word for it.

“Feeding our mother lines, we were training as straight men. The straight man’s was an honorable calling, a bit like that of the rodeo clown: despised by the ignorant masses, perhaps, but revered among experts who understood the skills required and the risks run. We children mastered the deliberate misunderstanding, the planted pun, the Gracie Allen know-nothing remark, which can make of any interlocutor an instant hero.

“How very gracious is the straight man!—or, in this case, the straight girl. She spreads before her friend a gift-wrapped, beribboned gag line he can claim for his own, if only he will pick it up instead of pausing to contemplate what a nitwit he’s talking to.”

—Annie Dillard, _An American Childhood_